HISTORY OF BOULT-AUX-BOIS

Here is a short history of Boult-aux-Bois, which you can explore in more detail in the work dedicated to it by a historian, Mr. Robert Cecconello: "" Traces du passé de Boult-aux-Bois "" published by Editions Terres Ardennaises (November 1999).

BOULT-AUX-BOIS: A VILLAGE IN THE HEART OF THE ARDENNES & THE HISTORY OF FRANCE

Boult-aux-Bois, a small village nestled in the heart of the Ardennes Argonne, on the road linking Vouziers to Stenay, is on the border between several historical regions, a situation which has meant that it has witnessed many events.

From the Middle Ages (when Boult-aux-bois was first mentioned) until the Revolution of 1789, the village was the seat of an important commandery, first held by the Templars, then by the Knights of Saint-Jean-de-Jérusalem. Some of its commanders, such as the famous Adrien de Wignacourt, left a lasting mark through their fame and their actions.

In the 20th century, Boult-aux-Bois was affected by two world wars. During World War I, the proximity of the Argonne Forest made it a strategic location, and during World War II, the village was in the path of the German advance. These periods have left traces in the local collective memory.

Boult-aux-Bois has also seen the growth and achievement of anonymous heroes, such as the young Clarisse LAURENT, and the village has been marked by the passage of a great writer (Emile Zola) whose pen touched its streets and permeated its landscapes.

""BOULT-AUX-BOIS"": THE ORIGINS OF THE NAME

The history of the name Boult-aux-Bois is a fascinating example of linguistic evolution over the centuries. Records reveal significant variations in the spelling of the name, reflecting both local pronunciation and the freedom of the clerics who recorded the documents. In the 12th century, the village was referred to as Bo (National Archives, 1196), and in the 13th century, it was spelled Booul (1246). Bou appeared in the 16th century, and in the 17th and 18th centuries, it was written Boux (notably in Terriers and notarial acts). Variants such as Boulx , Bouë , or Bouës also exist in documents of the time.

It is on the Cassini Map in the 18th century that we find the form Boult for the first time, which was truly consolidated in the 19th century. If the official spelling has evolved to become Boult , the local pronunciation often remains Bou .

The addition of "-aux-Bois" appears earlier in documents, from the beginning of the 17th century, probably signifying a geographical characteristic linked to the surrounding forest.

The name Boult itself remains mysterious in its origin. Some hypotheses suggest that "Boux" could derive from "bois", while others, influenced by the current form, link it to the word "birch" , a common tree in the region. Another theory suggests "Bo" , the oldest name, which could derive from "bodillum" or "bodillis" , Latin terms for a shelter or hut, perhaps a refuge in the woods. The name of the village could also come from the Latin " boscus ", meaning "wood", in reference to its forest environment.

However, these hypotheses, although plausible, do not yet allow us to identify with certainty the exact origin of the name Boult. Research is still ongoing, and each lead contributes to the complex history of this village.

THE BOULT FOREST TO THE AID OF THE ORDER OF MALTA AGAINST THE TURKS

Founded in the 12th century, the Order of the Hospitallers of Saint John of Jerusalem settled on the island of Rhodes at the beginning of the 14th century, where its knights became the fearsome guardians of the seas. By hunting down Barbary pirates and securing the coasts of the Near East, the Order fiercely defended Christian borders. Composed of the sons of the greatest families in Europe, mainly from France, the knights took vows of chastity, obedience and poverty, although the Order itself possessed immense wealth, inherited from the Templars. The Commandery of Boux was one of these possessions that financed the actions of the Order.

However, in the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire, at its height under Suleiman the Magnificent, threatened the Order. In 1522, after a heroic six-month siege, the Knights were forced to surrender Rhodes to the Ottomans. They then took refuge on the island of Malta, offered by Emperor Charles V. The Order of Saint John of Jerusalem thus became the Order of Malta, but the Ottoman threat remained. In 1557, under the authority of Grand Master Jean Parisot de La Valette, the Order strengthened the island's defenses with imposing fortifications.

To finance this defense, the Order exploited cultivated land (800 hectares in the commune of Boult-aux-bois alone) as well as high forests, such as the Boult forest. The latter, nationalized during the Revolution, became the state forest located at the gates of the village.

LOUIS XVI IN BOULT-AUX-BOIS: A MISSED MEETING!

… [FUTURE]

VALMY

… [FUTURE]

CLARISSE LAURENT

Clarisse LAURENT is not only one of the streets of the village, she is also and above all a young heroine of 19 years old. The story of Clarisse Laurent is a poignant testimony of courage, dedication and solidarity in the heart of tragedy.

In the 19th century, cholera caused several devastating waves across Europe. France was particularly hard hit by the 1832 epidemic, with a large concentration of cases in Paris, where the Prime Minister, Casimir Périer, succumbed to the disease. A new epidemic occurred between 1846 and 1851, and in 1849, Marshal Bugeaud also fell victim. That year, cholera also affected the Ardennes, and outbreaks continued for several years, affecting many localities, including Boult-aux-Bois.

Cholera arrived in Boult-aux-Bois in 1849, and the village, like so many others in the region, was hit hard. Fear and panic spread quickly, causing some residents to flee their homes, even abandoning sick relatives, for fear of contagion.

Only the intervention of the doctor sent by the sub-prefect and the commitment of a few courageous villagers made it possible to contain the epidemic.

Among these anonymous heroes, Clarisse Laurent, then aged 19, stood out for her courage and altruism. Living on Rue des Friches with her father and brothers, she had taken over the responsibilities of the home after her mother's death in the spring of the same year. As soon as the first cases appeared, young Clarisse threw herself fully into helping the sick, cleaning, caring for and comforting without ever worrying about her own safety.

The doctor of the time testified to her exceptional dedication: at the height of the crisis, Clarisse spent eight days and eight nights without sleep, providing care to cholera patients and helping to save many lives. Through her determination and compassion, she gave hope to her fellow citizens while the epidemic raged.

Sadly, as the disease receded, Clarisse succumbed to cholera on the night of October 9, 1849.

His death shocked the village, and on November 14, 1849, the municipal council paid him a solemn tribute, highlighting his courage and sacrifice.

The mayor even asked for financial aid to support his father, a navvy who was in great difficulty, demonstrating the collective gratitude towards this young girl with "sublime devotion".

However, this recognition was accompanied by a striking contrast: in this same deliberation, the mayor, one of the richest inhabitants of Boult-aux-Bois, demanded reimbursement of the expenses incurred to accommodate and feed the doctor sent by the sub-prefect. The sum requested, 45 francs, was unanimously approved by the municipal council.

EMILE ZOLA

Émile Zola passed through the village of Boult-aux-Bois on April 30, 1891, during his long journey from Reims to Sedan, with the aim of documenting, with his demanding method, the tragic journey of the French Army which ended, on September 1, 1870, with the disaster of Sedan. His travel diary, published in the collection "Terre humaine", gave a precise description of the Ardennes countryside at the end of the 19th century.

1918

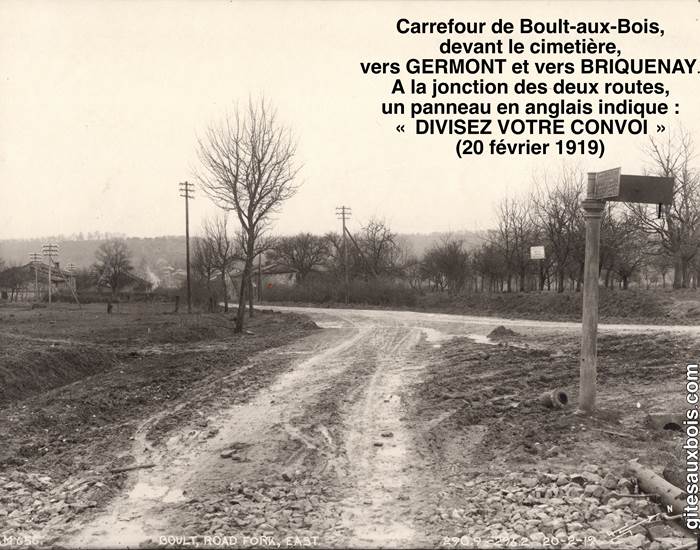

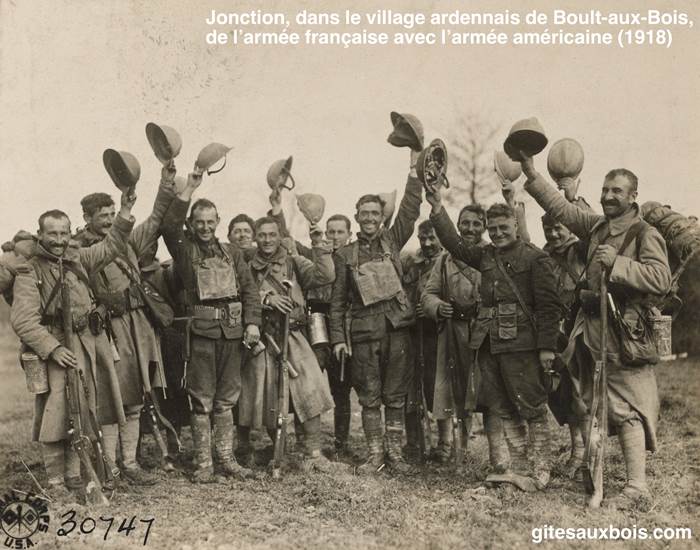

In 1918, in the final months of the First World War, Boult-aux-Bois witnessed a significant event: the meeting of the French and American armies. As the Allied offensive gathered momentum to push back the German forces, this peaceful village became a strategic crossing point for the soldiers.

The French troops, hardened by four years of grueling fighting, welcomed their American allies, who had come as reinforcements, with their enthusiasm and freshness. Soldiers from both nations crossed paths in the streets and meadows bordering the village. The scene, marked by the exchange of rations, awkward words in different languages, but above all fraternal handshakes, illustrated the union of the allied forces.

Curious and moved locals witnessed these moments of brotherhood between soldiers. For the villagers, this meeting was a bearer of hope, a tangible sign that the end of the war was approaching. The Americans impressed with their modern equipment and their enthusiasm, while the French shared their experience of the field and their determination to reconquer their territory.

Even today, Boult-aux-Bois remembers this episode as a moment of solidarity which marked the very last moments of the war.

Photographs of exceptional quality for the time, made possible by the Americans' sophisticated equipment, immortalized this memorable encounter. These shots, of a precision rare in 1918, capture the delighted faces of the French and American soldiers and the simple gestures of fraternity between allies.

MAY 40: THE GERMAN ATTACK

It is 1940, in the spring. The month of May is blooming in all its splendor. The first daffodils, bright yellow, decorate the green meadows. The swallows fly low, circling joyfully among the soldiers, mobilized a few months earlier to lead a "phoney war", while the storks, majestic, observe the world from the tall chimneys of the picturesque Alsatian villages.

Yet, a few cables away from this sweet tranquility, the shadow of war looms. With the return of good weather, Hitler has just given the signal for the great offensive. The German war machine, formidable and equipped with impressive destruction equipment, is preparing to rush across Belgium, and to penetrate French territory through a region that the French general staff, confident in the impassability of its relief, considered impenetrable: the Ardennes.

It is May 9, 1940, in the village of Pouru-aux-bois, located just 45 kilometers from Boult-aux-bois, in the immediate vicinity of Belgium and the fortified house that served as the setting for Michel Mitrani's film ("a balcony in the forest"), where the young Francis DEOM, son of farmers then aged 15, my grandfather, is the witness (like all the inhabitants of the Ardennes) of the surprise attack and the tragedy which is announced:

"We are going to plant potatoes today. The troops are on alert. The men have been given cartridges and the horses are to be saddled by 9 o'clock.

"If I looked at the packages a little," asks Mom. "It's always going to Canadas," answers Dad, "look at the packages if you want, but you have to come in the afternoon!"

We plant them with a hoe. I leave alone. "Where are you going?" the good women of the washhouse ask. "To the Canadas. Well yes, if it's the Germans who pull them up, we'll see it!"

I arrive, I work. It is splendid weather. May weather. Father Habary also arrives in a field not far from there.

- You know, he shouts, the Germans have entered Belgium!

- Ah!

- And then in Holland!

- Oh !

- And then, they bombed Brussels, Antwerp, Amsterdam and Namur!

- No kidding?

For my part, I don't believe a word of it. The Germans have already entered Belgium so many times! On any other occasion - false - I would have rushed to him to get news. Today, because it's true, I'm staying here.

- So, are we going to evacuate? I asked him then.

- Oh! Do you think so! he replies.

I start digging again. We can hear the sound of planes in the distance, towards Carignan or Montmédy.

Suddenly, and "ploc, plic, plac", a horseman appears over there, at the crossroads, near the customs post. Then another and another, and another. They take the border road and go into the fir trees. They walk in single file, in the ditch. Here is a machine gun, then an anti-tank.

That's it, I said to myself with a pang in my heart, they've left for Belgium.

And coward, I don't even go forward to say goodbye to them...

Dad came to join me. The morning is advancing. The troop always passes.

At eleven o'clock I quickly return to the country and rush down the Nourru four at a time. The soldiers have left. The Germans have attacked. It is time for the news. The Belgians are resisting victoriously. The Dutch are also resisting victoriously and the allies are advancing.

Everything is fine…

We return to these unfortunate potatoes with the horse and the sleigh. The weather is very nice.

And that's where the drama begins...

Suddenly, having arrived at the bottom of the Broue, we heard a snoring which gradually became formidable.

At 2000 meters, maybe 1500, here are planes and planes!

They are arranged in triangles, 7 per triangle, and three triangles go abreast to form (together) another triangle which juts out like a wedge.

There are gray ones in the middle and all white ones on the sides. They go fast and they are big.

Their extraordinarily throbbing noise overpowers the sound of the cast iron wheels of the sled that I purposely run over the stones. We go two kilometers with it above us.

The horse is very angry, he is dancing.

I counted 76 planes that disappeared behind the hills of Chiers and Meuse. The DCA had not fired...

A quarter of an hour later the buzzing came back, less loud it seemed. We were behind a wood, so we could hear them without seeing them.

Suddenly, "crack", several anti-aircraft shells burst dryly one after the other. And then, a minute later, no more, two formidable detonations shook the atmosphere and made us jump, immediately followed by several others, rapid, but so loud that they pierced our ears like anti-tank gunshots. Two planes appeared from behind the woods, one behind the other, 50 or 75 meters high, no more. They went faster than lightning, their machine guns barked furiously and the engines roared with a hellish noise. We lowered our heads instinctively, but the two monsters were already on the horizon. Their air movement made the branches of the wood shiver.

The bombers are now marching in the opposite direction and in a somewhat scattered order. In the valley, big gray clouds stretch, rise and slowly diffuse into the air. We breathe a smell of gunpowder. The anti-aircraft guns fire to the side so as not to lose the habit.

Then everything gradually calms down.

What were these two planes that had the crazy and dangerous idea of flying at 400 km/h at ground level while machine-gunning each other?

It was probably a French or Englishman who, having wanted to hinder the bombers, was himself attacked by a fighter from the German escort and went down to escape it.

The other followed him and was chasing him at ground level when we saw them.

Still, it is an incredible thing, this relative calm, and then, without transition, this hell which leaps, howls and disappears!

Driven by a dull worry, we return earlier than usual. Back home, we are told that Pourru has also been bombed. Several bombs have fallen, including one on a house near the school. There are victims. Who? How many? We don't know for sure.

We wonder what will happen."Me," said René, "it won't surprise me if in 15 days they tell us we have to evacuate!" Eh! Poor guy! In 15 days!

Our cart is at the sawmill, 300 meters from our house. We decide to go and get it and take it up, fearing the unexpected. I leave with my young friend Marcel who was in Pourru earlier and gave me a bomb fragment. Night falls. We hear nothing. We think about what is happening up there, between the Germans and the Belgians. But it does not occur to us that this is the last night in the country. Everything is calm, no troops are passing, no more planes, there is nothing more to fear!

Back home we find ourselves in the car column of the 11th Cuirassiers which is leaving to join the soldiers in Belgium, near Neufchâteau. A rolling stock has stopped and we question the cooks. They tell us that in Francheval there is an uninterrupted line of Belgian refugees. They come from Bouillon but because of Sedan they are diverted via Francheval and Douzy.

We are beginning to understand that the situation is not as clear as 795 says...

The whole evening is spent talking in the streets...

It's late, maybe eleven thirty... I just went to bed with the intuition that it won't be for long; I doze off.

Suddenly, as if in a dream, I hear a knock on the door opposite, that of the rural policeman: "Philomin, Philomin, get up! For God's sake!" I hear voices, muffled gallops.

I jump out of bed and go outside. It is pitch black and very cold. A shadow walks across the square with a bell and stops in the middle: "Ding, Ding, Ding, Ding!" Doors open silently. "Ding, Ding, Ding!"

"By order of the Military Authority, the village must be evacuated to-ta-ly at – two o'clock in the morning – at the latest."

That's it. Two in the morning! It's midnight.

The doors close without a word.

Behind the Pierreuse hill, searchlights nervously search the sky.

There! It's done. We've been dreading this cursed evacuation for so long, we've been waiting for it for so long! There it is, simply, hideously. Two hours!

I go home. My parents have already removed the mattresses from the bed and are making bundles of bedding by putting the comforter and the mattress in the middle, then the sheets, and the blankets on top, all rolled up and tied. The trunks are already ready.

For an hour it is a feverish activity to prepare the few best objects. Fortunately we thought in advance about what to take and what to leave!

I thought about taking my books and papers that I value most. I had also carefully packed a piece of the Pourru bells broken by the Prussians in 17.

We pack provisions, especially coffee, precious coffee! Snacks, pasta, bread, eggs, bacon, sugar, rice… In addition to linen and clothes, some kitchen utensils that can be used on the road…

And then what! We would like to take everything, take everything away! Well, no! We can't!

30 kg! Let's think about it! 30 kg, that makes 90, let's say 100 kilos. It's not heavy! It's not big!

But I have to go to Aunt Aline's, to help her pack too. I spend half an hour there.

It's now half past one. Only thirty minutes left!

The night is very dark. Although the whole village is packing, nothing can be heard, and my footsteps sound on the road. Earlier I was shivering, but now it is almost mild. Is this already the habit? No, because I feel a great worry. What is going to happen soon?...

Dad sends me to offer my services to a neighbor, Lucien Dazy, who must have difficulty charging.

We bring his cart in front of the house. As he is still mounted to cart the wood, I help him to refill it, with boards, ladders and stakes. Then another neighbor also arrives to help and I come back.

Two o'clock in the morning. Nobody leaves, nobody has left.

To hell with the Military Authority and its absurd orders!

How do they expect us to liquidate the fruits of twenty years in two hours?

Francis was to celebrate his 16th birthday a few days later, on May 18, 1940. This year, as well as the following ones, he would not celebrate it at home: the village of Pouru-aux-bois, urgently evacuated by its inhabitants, would be taken a few days later by the Germans, before the latter continued their rapid advance towards the south of the Ardennes, towards Boult-aux-Bois:

" The first French villages were bloodied before being conquered.

The three regiments of foreign volunteers, trained in Barcarès, were relieved from their positions, to be sent to the most threatened sectors:

- the 22nd regiment in the Somme: the battle of Péronne;

- the 23rd regiment in the Soissons region;

- the 21st in the Ardennes.

German planes do not leave the sky. They bomb roads, bridges and railway stations.

The 21st regiment moves with great difficulty, traveling by train, truck and walking a lot. It covers dozens of kilometers every day.

We are preparing for trench warfare and we have to dig hundreds of kilometers...

We are approaching the Ardennes. The route passes through Long-champs, Chaumont, Erize-la-Grande, after Sainte-Ménéhould, Cernay, le Morthome, up to the surroundings of the village of Boult-aux-Bois .

There, we stop in the small wood, not far from the village, and we find ourselves facing the enemy.

The village of Boult-aux-Bois is occupied by the Germans, ours look towards the little white houses, with red tiled roofs, surrounded by fields resplendent with all colors. It is here, in the small woods that Srolek's company, the "CA1." will deliver its first battle. Ours, although exhausted by a long march, quickly occupy the combat positions.

The Germans began by bombarding the forest with their artillery; the bombs exploded on all sides, riddling the earth, and throwing the trunks of the trees into the air.

Then they attack, covered by heavy machine gun fire.

We count our first dead. Here is a comrade with whom you lived, whom you loved like a brother, he lies bleeding in your arms, and confides to you his last words... you, you must leave and abandon him forever...

It was a short but bloody fight, our men were forced to withdraw.

The next day, the battalion occupied new positions in the village of Petites-Armoises, individual holes were dug, the 25 cannon and mortars were installed, and we fortified ourselves.

(""Our Will"", Bulletin of the Union of Jewish Volunteers and Veterans 1939-1945, October-November 1989, No. 2).

Even today, the Boult-aux-Bois forest bears the scars of its past, lastingly marked by the scars of its trenches and numerous shell holes.